As Nigeria marked its 65th Independence anniversary, the air was heavy with both nostalgia and unease. The celebrations were subdued by a familiar refrain, the urgent, almost desperate, call for genuine electoral reform.

For many Nigerians, democracy remains suspended in a cycle of promise and betrayal, where each election rekindles hope yet ends with controversy.

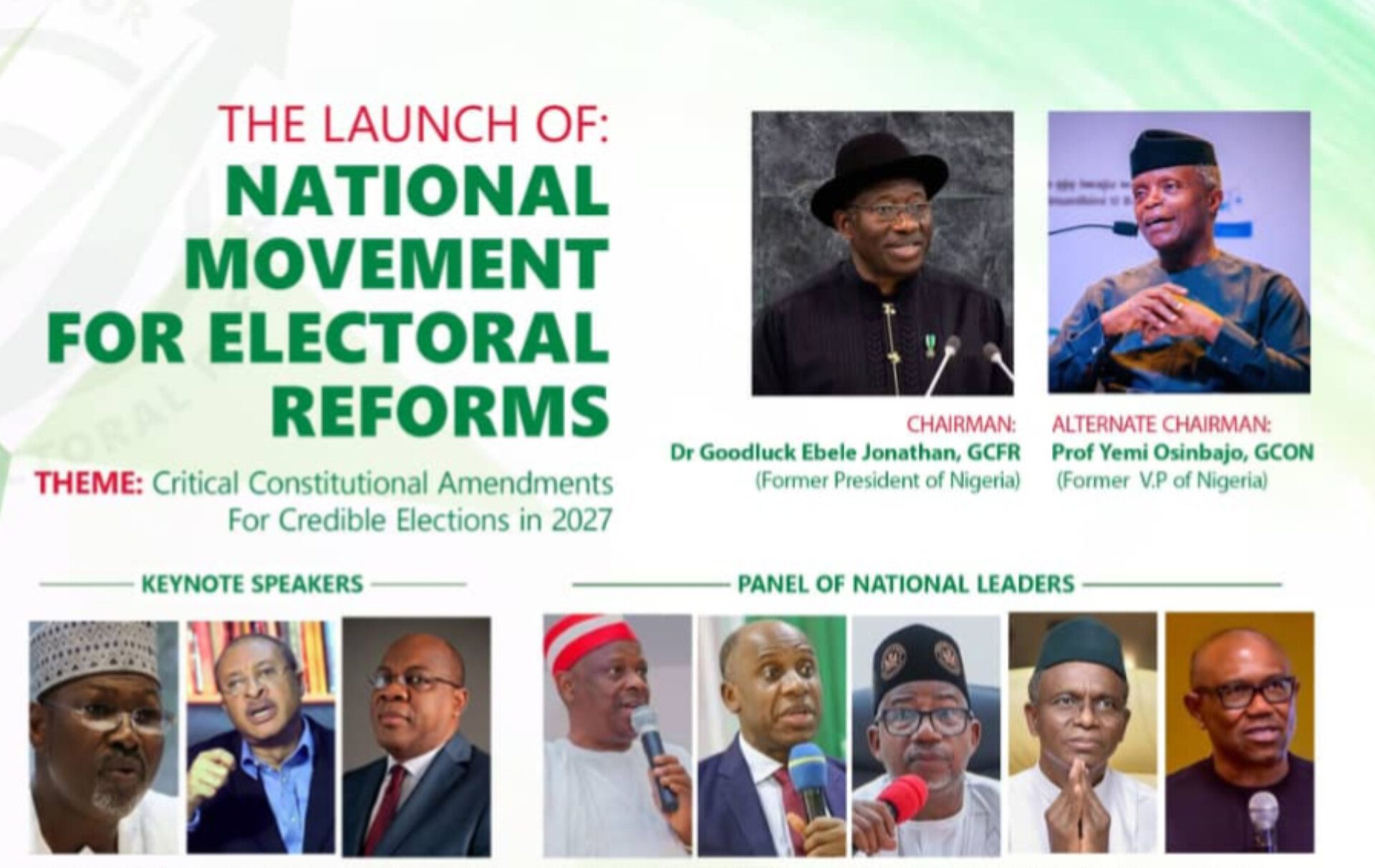

At a virtual Electoral Reform Summit convened to set the agenda for 2027, the voices of discontent rang loud.

From fiery critiques to sober policy prescriptions, political figures, civil society leaders, and reform advocates converged on one message: without urgent reform, Nigeria’s democracy risks collapse under the weight of mistrust.

Former Minister of Transportation and one-time presidential hopeful, Rotimi Amaechi did not mince words. His intervention was blunt, even fatalistic.

“There is absolutely nothing anybody can do about electoral reform in Nigeria, especially under this present government — absolutely nothing,” he declared.

Amaechi’s skepticism cut across two layers: the unwillingness of the political class to reform a system from which it benefits, and what he described as the “climate of fear” surrounding President Bola Tinubu’s government.

He pointed fingers not only at incumbents but also at past leaders and reform advocates now clamoring for change.

“Most of the people invited here today were once in government. What did they do when they had the opportunity? If they had acted then, we wouldn’t be here now,” he said, in a sharp rebuke that underscored the cyclical nature of Nigeria’s reform discourse.

If Amaechi embodied cynicism, Dr. Oby Ezekwesili, former Minister of Education, offered a blueprint grounded in institutional independence and accountability. She called for direct statutory funding for INEC, removing its dependence on executive goodwill.

But Ezekwesili went further:

INEC, she argued, must be compelled to justify its spending and conduct, with prosecutorial powers to sanction politicians who undermine elections.

The judiciary must face systemic accountability, including automated assignment of election petitions and firmer discipline for errant judges.

Civil society, not the executive, should be central to the appointment of electoral commissioners.

Her message was clear: reform is not just about laws; it’s about restructuring power away from entrenched interests.

For Peter Obi, former Labour Party presidential candidate, the heart of the matter lay in restoring the people’s faith.

“It would be a double tragedy if Nigerians, after years of flawed leadership, also lose faith in elections,” Obi warned. “Democracy can only thrive when the people’s mandate is respected.”

Obi pressed for secure electronic transmission of results from polling units — a demand echoing the frustrations of millions who believe their votes vanish in opaque collation centers. He also backed proposals to curb post-election defections, borrowing from Ghana and South Africa where crossing party lines after elections carries strict consequences.

Political economist Prof. Pat Utomi reminded the summit that reforms cannot succeed without citizen vigilance and civic education. Nigeria, he argued, cannot outsource democracy to elites while the masses remain uninformed and vulnerable to vote-buying.

The summit’s communiqués echoed this concern: until citizens see democracy as their personal responsibility, electoral reforms risk remaining paper promises.

From the lessons of #EndSARS to grassroots voter education, participants called for leadership training and civic awareness campaigns that would “equip every Nigerian with at least 70% knowledge of personal leadership and civic responsibility.”

Across the sessions, certain priorities crystallized into a reform wishlist to include Mandatory electronic transmission of results with legal safeguards, diaspora voting, to enfranchise millions of Nigerians abroad, Independent oversight of INEC’s budget and operations and proportional representation and reserved seats for women and vulnerable groups.

Others are, clear anti-defection rules, to protect voters’ mandates and stronger civic education, to inoculate citizens against inducements and apathy.

Organizers of the summit were candid: the window for reform is narrow. With the 2027 elections less than two years away, the October 21 physical session in Abuja will consolidate these proposals into a consensus document for lobbying, advocacy, and mobilization.

Yet the underlying question lingers: will Nigeria’s ruling class — the very beneficiaries of a broken system — have the will to dismantle it?

The contrast between Amaechi’s despair and Ezekwesili’s policy optimism mirrors the national mood: a people caught between cynicism and hope. On one side, decades of failed promises erode trust.

On the other, the relentless push by reformers signals that Nigerians are unwilling to surrender their democratic dream.

As one speaker put it bluntly at the close of the summit:

“If we fail to act now, we risk recycling the same failures that have eroded public faith in democracy. But if we act, the 2027 elections could mark the beginning of a rebirth.”

For now, Nigeria stands at a crossroads — its democracy fragile, its future uncertain, its citizens restless for change.