By John Akubo

On Wednesday in Abeokuta, a familiar bond was quietly rekindled. Former President Olusegun Obasanjo received his long-time ally, former Jigawa State Governor Dr. Sule Lamido, at the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library (OOPL). What might have seemed a routine courtesy call carried undertones far deeper: reflection on Nigeria’s past struggles, anxiety about its fragile present, and pointed questions about the nation’s uncertain future.

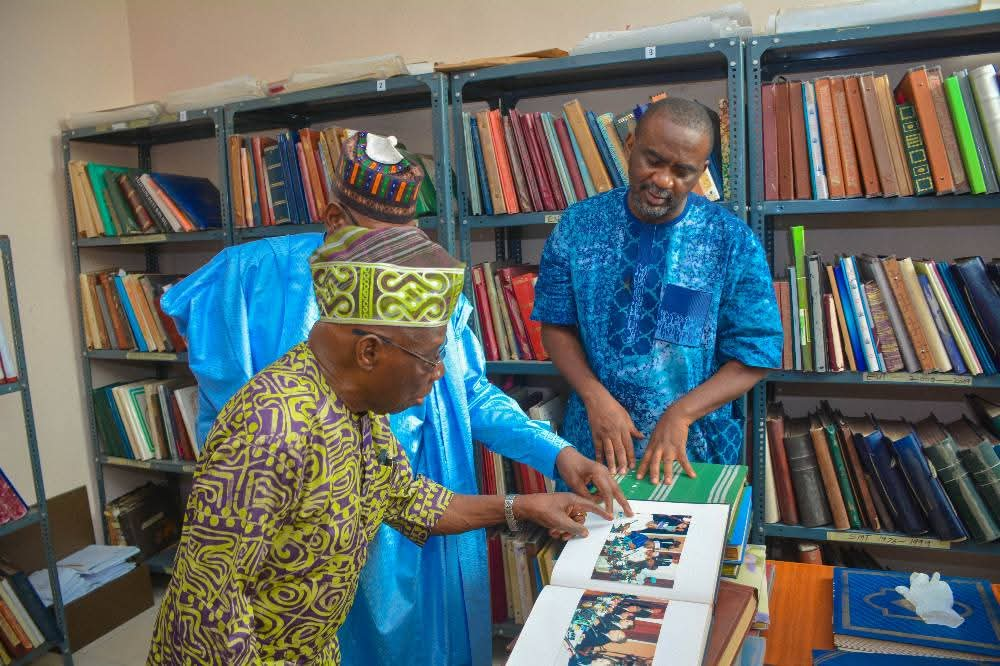

The visit was intimate but symbolic. Obasanjo personally guided Lamido through the sprawling OOPL — part museum, part archive, part leadership school. Each corner tells the story of Nigeria’s turbulent march from colonialism through military dictatorship to a fledgling democracy. As Lamido lingered among the exhibits, photographs of Obasanjo in prison, documents from his years as military ruler, and artifacts from global peace missions, the narrative of one man’s life blended with that of the nation itself.

Obasanjo and Lamido share more than political affiliation; theirs is a bond forged in history and struggle. As Foreign Minister between 1999 and 2003, Lamido was a key player in Obasanjo’s post-military civilian presidency, when Nigeria sought to shed its pariah image. The duo embarked on diplomatic shuttles from Washington to Beijing, lobbying for debt relief, trade partnerships, and Nigeria’s reacceptance into the global community.

Yet the relationship went beyond official duty. Lamido became one of Obasanjo’s protégés — what the former President would later describe as “my own experiment in leadership cultivation.” When Obasanjo famously admitted that he had “forced Lamido on Jigawa” as governor in 2007, it was not merely political godfatherism. “If you can say, yes, Obasanjo forced this one on us, it is a good forcing,” he told Jigawa leaders, insisting that Lamido had justified the faith reposed in him.

The Abeokuta encounter was more than a nostalgic reunion. It was a return to an old debate that both men have championed for decades: the centrality of leadership in Nigeria’s destiny.

For Obasanjo, leadership has always been the fulcrum of Africa’s crises and possibilities. Addressing Lamido during the visit, he reiterated what he has long argued — that the continent’s volatility is not about lack of resources or talent, but about a “profound leadership deficit.” Leadership, he says, is not about occupying office but about vision, character, and the courage to make unpopular decisions for the greater good.

Lamido, too, has long aligned with that conviction. Known as a fiery defender of the talakawas, the ordinary citizens of the North, he has framed his politics around accountability and people-centered governance. In Jigawa, he sought to combine Obasanjo’s ethos of reform with grassroots pragmatism, earning him recognition as one of the more reform-minded governors of his era.

Observers say the Abeokuta meeting could not have come at a more poignant time. Nigeria is navigating one of its most trying periods since 1999: spiraling inflation, unemployment, resurgent insecurity, and widespread cynicism about politics. The same questions Obasanjo and Lamido wrestled with two decades ago, how to restore legitimacy to governance, how to give Nigerians faith in democracy — are once again on the table.

By walking Lamido through the OOPL and the Olusegun Obasanjo Leadership Institute, Obasanjo seemed to be restating his lifelong mission: to mentor a new generation of leaders who understand that power without moral grounding is a hollow pursuit. For Lamido, the visit was also a reminder of his own place in that historical continuum — a bridge between the Obasanjo era and a political future yet undefined.

The two men’s shared history is layered with personal anecdotes that shed light on Nigeria’s political evolution. When Obasanjo penned the foreword to Lamido’s book, Being True to Myself, earlier this year, it was not only a gesture of friendship but a public validation of Lamido’s political philosophy.

Their camaraderie dates back to 1999, when Obasanjo’s decision to appoint Lamido as Foreign Minister strained his ties with Lamido’s patron, Abubakar Rimi, who had coveted the post. In 2003, Lamido cried foul when the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) lost Jigawa, insisting the election had been manipulated. By 2007, however, he emerged victorious, with Obasanjo’s backing proving decisive.

Through those ups and downs, what has endured is a shared outlook: that Nigeria cannot progress without leaders who combine vision with integrity, discipline with compassion.

The Abeokuta reunion, therefore, was not merely ceremonial. It was a tacit commentary on today’s political class, many of whom are consumed by the trappings of office but detached from the burdens of leadership. As Obasanjo bluntly put it during his Jigawa summit appearance in 2013, “You can help anybody to find a job but you cannot help anybody to do the job.”

For Nigeria’s younger generation — restless, disenchanted, and searching for models of leadership — the symbolism of Lamido and Obasanjo standing together again is powerful. It recalls a period when politics was anchored, however imperfectly, on ideas of service and national renewal.

Yet nostalgia alone cannot save Nigeria. The real question raised by the Abeokuta meeting is whether such conversations can inspire practical pathways out of the current malaise. With youth unemployment soaring, insecurity spreading, and faith in democracy thinning, the need for leadership reform is urgent.

Obasanjo’s new Leadership Institute — envisioned as a school for grooming visionary, ethical leaders — is his latest contribution to that cause. For Lamido, who remains a respected elder statesman within the PDP, the challenge is how to translate reflection into action, mentoring into movement, and history into a catalyst for renewal.

Ultimately, the reunion was not about two men reliving their past but about two veterans offering a mirror to Nigeria’s present. By revisiting the milestones of their shared journey — from global diplomacy to domestic reform — Obasanjo and Lamido were, in effect, challenging Nigeria to confront its leadership dilemma with honesty.

For a country where governance has too often been reduced to transactional politics, their Abeokuta encounter was a reminder that leadership, at its best, is about vision, sacrifice, and the courage to act when history demands it.