By Harrison Tombra

Before the truce came the tremor.

When President Bola Ahmed Tinubu declared emergency rule in Rivers State and appointed Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas (rtd) as Sole Administrator on March 18, 2025, it felt like a political earthquake had just struck the state. Governance had ground to a halt. Budgets were frozen. Public institutions were paralysed by a bitter feud between Governor Siminalayi Fubara and his political benefactor, Nyesom Wike. The State Assembly was factionalised, with each side issuing contradictory laws and threats. To many, Rivers stood on the brink of institutional collapse.

Fast forward to the present, and the story has changed dramatically. In what is now being celebrated as a critical breakthrough for stability, the major players in Rivers politics—Governor Fubara, former Governor Wike, and members of the State Assembly—have agreed to a truce midwifed by President Tinubu. For the first time in nearly a year, the state seems poised to return to a path of reconciliation and normalcy.

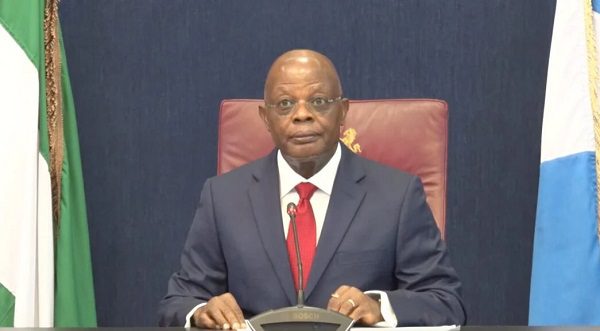

But that peace did not emerge from a vacuum. It was not conjured from a conference table. It was made possible by a deliberate, disciplined, and quiet groundwork laid over the past months by a man many initially doubted—Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas. This article examines how Ibas’ tenure created the enabling environment for Rivers’ political actors to put down their swords and prioritise the people.

To understand the scale of his achievement, we must remember what Ibas inherited. Ministries were dormant. Civil servants were owed salaries. Local government councils were functioning in name only. Pension arrears had piled up, while health facilities and schools suffered neglect. Public morale was at its lowest ebb. The state’s reputation in Abuja had become one of infamy and ridicule.

Rather than wield his mandate with bravado or political vengeance, Ibas made a calculated choice: to stabilise first, then restore. That decision has made all the difference.

His first weeks were focused on diagnostics. He summoned permanent secretaries, council chairpersons, and senior technocrats to provide operational and financial records—a rare move in a system often built on opacity. This baseline assessment allowed his administration to understand the scope of damage and begin structured repairs.

He followed this with a bold but necessary step: revising the state’s 2025 budget. The revised ₦1.846 trillion fiscal plan was not about political optics. It was about correcting distortions, accommodating unrecorded obligations, and setting a realistic path to recovery. While critics questioned the amount, few could argue with the priorities—healthcare, education, youth and women empowerment, climate resilience, and pension payments. It was the first real signal that governance was back on the front burner.

Then came perhaps his most impactful policy—forcing local government accountability. For the first time in recent memory, LGAs were asked to submit two years’ worth of activity and financial reports. This was not a witch-hunt. It was a message: impunity is no longer the default. This move unlocked a flurry of local actions—waste management resumed, health posts reopened, and school monitoring was reactivated.

But beyond policy, Ibas’ most subtle achievement was psychological. He shifted the tone of governance in Rivers State—from confrontational to constructive, from chaotic to consistent. His “few words, many actions” style avoided the usual bombast associated with emergency rule. Instead, it delivered results in ways that left civil servants motivated, public workers respected, and citizens cautiously optimistic.

Media engagement under his leadership also played a defining role in softening the political climate. Rather than hijack the airwaves or sponsor propaganda wars, Ibas’ administration focused on strategic communication—radio jingles promoting peace and unity, town hall meetings for inclusive dialogue, and capacity-building for local journalists to improve ethical reporting and reduce political sensationalism.

All of these culminated in a significant shift: Rivers people began to feel heard again. Public discourse, which had once been dominated by anger and fear, began to reflect hope. Town hall meetings, especially in Rivers East, drew strong participation. Community elders praised the new tone of leadership. Youth leaders spoke of being included. Civil society organisations were invited to contribute ideas, not just react to crises.

When President Tinubu finally convened the parties and brokered the peace accord between Wike, Fubara, and the State Assembly members, the ground had already been softened by Ibas’ stewardship. It is no coincidence that the agreement came at a time when institutions had started working again and the political temperature had visibly cooled.

Leadership, in its truest form, is not just about crisis response—it is about crisis prevention. While the reconciliation deal now promises a peaceful transition out of the emergency phase, the role Ibas played in making that peace possible must not be overlooked.

There were no victory dances, no billboards proclaiming his name, and no social media campaigns burnishing his image. And yet, in these months of emergency governance, Ibas has achieved what years of political chest-thumping could not—he restored credibility to governance.

That credibility was also evident in his federal engagements. Ministries and agencies that had previously distanced themselves from Rivers began returning to the state with support—technical aid, health collaborations, road assessments. Abuja was no longer wary; it had found a reliable interlocutor in Ibas. And that trust extended beyond federal corridors into diplomatic and donor networks, many of whom resumed quiet re-engagement with the state.

It is also important to highlight that Ibas never positioned himself as a political alternative or successor. He maintained neutrality. He kept communication open with all camps. This is partly why he was able to govern without triggering resistance or backlash from entrenched interests.

Now that a truce has been reached, the question is not whether Ibas will remain in office beyond the emergency period. The question is what Rivers will do with the foundation he has laid. The reconciliation deal is fragile, as all truces are. But the institutional stability Ibas reintroduced offers a framework for rebuilding trust across political divides.

That trust is the most important inheritance Rivers can take from this period. Trust in processes. Trust in systems. Trust in a government that works for its people—not in spite of them. For all the legal controversies that may continue to surround his appointment, this much is clear: Ibas gave Rivers the rarest gift in politics—stability without strife.

As the state prepares to transition back to a democratically guided administration, it is imperative that the culture of quiet delivery, fiscal transparency, and inclusive governance be preserved. Whether under Governor Fubara, Wike’s renewed influence, or another arrangement, Rivers cannot afford a return to the chaos from which it just emerged.

Vice Admiral Ibas may not seek the limelight. But in guiding Rivers from conflict to collaboration, he has earned his place in the annals of the state’s most consequential administrators. The peace deal may bear the signatures of the political gladiators, but its real author is the man who made it possible—without raising his voice, without picking a side, and without missing a step.

Harrison Tombra is a public affairs analyst and writes from Abuja.